- Home

- Stephen Halliday

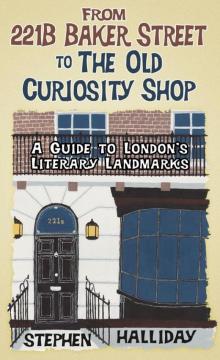

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop Page 12

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop Read online

Page 12

In the same area, at about the same time, lived the Wilcox and Schlegel families of E.M. Forster’s novel Howard’s End. They lived in the fictional Wickham Place, the Schlegel family’s house being:

… fairly quiet, for a lofty promontory of buildings separated it from the main thoroughfare [i.e. Brompton Road]. One had the sense of a backwater, or rather of an estuary, whose waters flowed in from the invisible sea and ebbed into a profound silence while the waves without were still beating. Though the promontory consisted of flats – expensive, with cavernous entrance halls, full of concierge and palms – it fulfilled its purpose, and gained for the older houses opposite a certain measure of peace.

The flat in ‘Wickham Mansions’ occupied by the more commercially minded Wilcox family thus acts as a protective shield for the more sensitive and aesthetic Schlegels, the destinies of the two families becoming intertwined with tragic consequences. Many of the streets behind Brompton Road still have this combination of flats and older, more elegant houses.

Ranelagh Gardens in Chelsea opened in 1742 as a place of respectable entertainment, with an ornamental lake, booths for drinking tea and wine, a Chinese pavilion and an orchestra stand where Mozart played during a visit to London. Admission cost 2s 6d (12½p, tea and coffee included) which excluded all but the well-to-do. In The Expedition of Humphry Clinker, Tobias Smollett described it as ‘the enchanted palace of a genius … crowded with the great, the rich, the gay, the happy and the fair’. Edward Gibbon considered it ‘the most convenient place for courtships of every kind’ and Canaletto painted it. It closed in 1803 and was incorporated in the grounds of the Royal Hospital, Chelsea at the eastern side, adjacent to Chelsea Bridge Road.

THE CHELSEA EMBANKMENT

To the west, on the banks of the Thames, is Cheyne Walk, long the home of Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) and close by, on its corner with Danvers Street, is Sir Thomas More’s House, Crosby Place (which was referred to in Chapter 3) and relocated here in 1908.

A statue of the author of Utopia may be seen in the grounds of Chelsea Old Church on the corner of Old Church Street and the Chelsea Embankment. The church, close to the present site of Crosby House, dates from the fourteenth century and contains many mementoes to Sir Thomas More. He rebuilt the south chapel in 1528 for his own private worship and his first wife is buried here together with a tribute to Alice, his second wife and her devotion to his children from his first marriage:

To them such love was by Alicia shown

In stepmothers, a virtue rarely known,

The world believed the children were her own.

In his novel Murphy, published in 1938, Samuel Beckett refers to the clock of Chelsea Old Church which ‘ground out grudgingly the hour of ten’, no doubt heard during Beckett’s stay in London in the 1930s.

A short distance to the north, in Sydney Street across the King’s Road, is St Luke’s church, a magnificent neo-Gothic building constructed in the 1820s because Chelsea Old Church was too small for the growing population of Chelsea. Charles Dickens married Catherine Hogarth in this church on 2 April 1836, the rector being the brother of the Duke of Wellington.

SLOANE STREET

A short distance to the east, along the King’s Road, is Radnor Walk where Sir John Betjeman lived after moving from Cloth Fair in 1972, and he set a number of his poems in the area. He sometimes worshipped at Holy Trinity, Sloane Street, close to Sloane Square Underground station, which was built in 1888–91 by the Victorian architect John Sedding. It is a striking example of the Arts and Crafts style, with stained glass by William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones. Damaged by incendiary bombs in the Second World War, it was restored but its huge size (it is actually wider than St Paul’s Cathedral) led the Church Commissioners to propose demolishing it and replacing it with a smaller building. John Betjeman led a successful campaign to preserve it and it now thrives with a large congregation and a strong reputation for fine music. The building is worth visiting for its own sake, its architecture celebrated in Betjeman’s poem ‘Holy Trinity Sloane Street’:

Holy Trinity in Sloane Street was where John Betjeman worshipped. (Amanda Slater)

The tall red house soars upward to the stars,

The doors are chased with sardonyx and gold,

And in the long white room

Thin drapery draws backward to unfold

Cadogan square between the window bars

And Whistler’s mother knitting in the gloom.

Cadogan Square, nearby, is the site of the Cadogan Hotel (75 Sloane Street) which is remembered as the site of Oscar Wilde’s arrest following his unsuccessful attempt to sue the Marquess of Queensberry for slander. That event, too, was marked by Betjeman’s poem ‘The Arrest of Oscar Wilde at the Cadogan Hotel’:

Mr Woilde, we ’ave come to tew take yew

Where felons and criminals dwell;

We must ask yew tew leave with us quoietly

For this is the Cadogan Hotel.

STAMFORD BRIDGE

Further to the west is Stamford Bridge, the home of Chelsea Football Club, which in July 2005 was featured in a book called Incendiary by the novelist Chris Cleave. It takes the form of a correspondence with Osama Bin Laden and culminates in a terrorist attack on a football match between the London rivals Chelsea and Arsenal in which many are killed, including the narrator’s young son. The publication of the book was much heralded, not least by posters on Underground stations, and scheduled for 7 July. As London celebrated the award of the 2012 Olympics to London, announced on the day before the launch of Incendiary, fiction became fact as four suicide bombers launched attacks on the Underground and bus network, killing fifty-two Londoners and injuring many more. The posters were hastily removed and the publication of the book delayed, though it was eventually published with success and became a feature film.

HANS PLACE

In 1813–14 Jane Austen stayed at No. 23 Hans Place, Knightsbridge (marked by a Blue Plaque) and it was during this time that she was invited to Carlton House to meet an admirer of her writings, the Prince Regent, who suggested that she might dedicate Emma to him. This ‘honour’ was received with some misgivings by the author who had written critically of the Prince’s treatment of his wife, Princess Charlotte, though the latter’s marital behaviour was not without blemish since she travelled around Europe with a young Italian lover for company. Following a long and often amusing correspondence with Mr Clarke, the Prince’s librarian, they agreed on the following wording:

To His Royal Highness, the Prince Regent,

This work is, by His Royal Highness’s Permission

Most respectfully dedicated

By his Royal Highness’s Dutiful and Obedient Humble Servant,

THE AUTHOR

8

THE

EAST END

Dickens makes comparatively few references to the industrial and commercial life of London, though two of his novels, Dombey and Son and Our Mutual Friend, have several episodes set in the heart of London’s dockland. In Dombey and Son Captain Cuttle ‘lived on the brink of a little canal near the India docks, where there was a swivel bridge which opened now and then to let some wandering monster of a ship to come wandering up the street like a stranded Leviathan’. Captain Cuttle’s home could be almost anywhere on the Isle of Dogs and if he were living there now he would presumably be living in one of the luxury flats, his yacht moored in one of the marinas into which the old docks have been transformed. He would be working in one of the banks whose skyscrapers dominate the landscape. He might occasionally see Lizzie Hexam, from Our Mutual Friend, rowing along the river with her father Gaffer, a Thames waterman who makes his living by finding and robbing corpses that he drags from the river. Gaffer lives on the river bank at Limehouse, as does his fellow scavenger (and competitor) Rogue Riderhood. Gaffer’s house is conical in shape and looks like a derelict windmill which has lost its sails.

Limehouse Basin, a marina with a lock which connects the Regent’s Canal to th

e Thames, is now the home of flats and luxury yachts, and separated from the river by Narrow Street in which, at No. 76, is located a riverside pub called ‘The Grapes’. It has been on this site since 1720 and has resisted all attempts to subject it to the redevelopment which has overwhelmed this part of London. It has been identified by some as the model for Dickens’s ‘The Six Jolly Fellowship Porters’, not least because of stories that watermen, like Gaffer Hexam, would drown drunks in the river, empty their pockets and then sell their corpses for dissection by medical schools. In tribute, ‘The Grapes’ now has a ‘Dickens Bar’.

SHOREDITCH

The East End was also the subject of writers concerned with London’s impoverished and criminal classes. E.A. Morrison’s book Child of the Jago, published in 1896, was based on the ‘Old Nichol’ slum to the east of Shoreditch High Street, its former site now marked by Old Nichol Street. The author, Arthur Morrison (1863–1945), was born in nearby Poplar and wrote from experience, claiming in his preface to the novel that he had in mind ‘a place in Shoreditch, where children were born and reared in circumstances which gave them no reasonable chance of living decent lives: where they were born foredamned to a criminal or semi-criminal career’. The central character, Dicky Perrott, is the son of a weak mother and a n’er-do-well, drunken father. Dicky is led into a life of crime working for Arthur Weech, a Fagin-like figure who employs children to steal for him. Dicky is told that he has to choose between gaol, the gallows, or becoming one of the ‘Igh Mob’, the successful criminals whose rival gangs dominate the Jago in an atmosphere reminiscent of the influence in the area of the Krays in the 1950s and 1960s.

At the time that Morrison’s book appeared there worked in the area the Revd Arthur Osborne Jay (1858–1945), vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Shoreditch, who turned his church into a refuge for the homeless and a youth and sports club for young, rootless people. In Child of the Jago Jay appears as Friar Sturt, whose attempts to rescue Dicky from his life of crime are frustrated by Weech. Dicky is eventually killed during a gang fight at the age of 17. Morrison’s work was much criticised at the time for its uncompromising account of life in one of London’s most deprived areas, one critic claiming: ‘The original of the Jago has, it is admitted, ceased to exist. But I will make bold to say that, as described by Mr Morrison, it never did exist.’ Yet the work of Henry Mayhew, published in London Labour and the London Poor and later of Charles Booth, Life and Labour of the people of London showed that Morrison’s account, though fictional, reflected reality. And the impact of the novel was such that the terms ‘Nichol’ and ‘Jago’ became synonyms.

Bethnal Green was, for a while, the home of Sikes and Nancy in Oliver Twist. Much of the area was destroyed by bombing or demolished in slum clearance measures after 1945, but many of the streets mentioned in Morrison’s work, notably Old Nichol Street, Boundary Street, Bethnal Green Road and Shoreditch High Street, may still be seen. Morrison also wrote a series of articles and stories on similar themes for Macmillan’s Magazine which were later published as Tales of Mean Streets.

Matthew Arnold, whose verses on Kensington Gardens have been noted, wrote less flatteringly of Bethnal Green and of the fate of impoverished silk weavers in Spitalfields in his poem ‘East London’:

’Twas August, and the fierce sun overhead

Smote on the squalid streets of Bethnal Green,

And the pale weaver, through his windows seen

In Spitalfields looked twice dispirited.

Samuel Pickwick made one of his rare excursions to the East End when he and his companions visited the United Grand Junction Ebenezer Temperance Association, which was to be found in Brick Lane, Shoreditch.

Brick Lane itself gives its name to the title of Monica Ali’s novel Brick Lane, with its rather unflattering portrait of the Bangladeshi community which predominates in the area. Shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize in 2003, Germaine Greer was amongst those who criticised the book, claiming that it had created ‘a defining caricature’ of part of the Bangladeshi community. The book was later made into a film in 2007.

WHITECHAPEL

South of Shoreditch, in the Whitechapel area of Tower Hamlets, was a building which features in the works of Jack London (1876–1916) and George Orwell (1903–50). This was Tower House, which was built by the philanthropist Montagu William Lowry-Corry (1838–1903), a grandson of the Earl of Shaftesbury from whom he perhaps inherited his philanthropic genes. Lowry-Corry worked as private secretary to Benjamin Disraeli and was made Baron Rowton in 1880 when Disraeli left office. In 1890 Rowton donated £30,000 of his considerable fortune to build and run decent lodging houses for working men, providing such luxuries as clean sheets, hot baths and laundry facilities. The best known ‘Rowton House’ was in Fieldgate Street, Whitechapel. Jack London was one of its early residents and in his work The People of the Abyss he described it as ‘the Monster Doss House’ and wrote that it was ‘full of life that was degrading and unwholesome’. George Orwell, in Down and Out in Paris and London was much more appreciative, recording that:

The best lodging houses are the Rowton houses where the charge is a shilling, for which you get a cubicle to yourself and the use of excellent bathrooms. You can also pay half a crown for a special, which is practically hotel accommodation. The Rowton houses are splendid buildings and the only objection to them is the strict discipline with rules against cooking, card-playing etc.

Tower House still exists at No. 81 Fieldgate Street, E1, behind the East London mosque, though it has now been converted into luxury flats. The only Rowton house still in use as a lodging house is Arlington House in Camden. Situated at 220 Arlington Road, it has recently been extensively refurbished and was for a time the home of the Irish writer Brendan Behan.

9

WHERE TAXIS DON’T GO: SOUTH OF THE RIVER

The humorous expression sometimes attributed to taxi drivers, ‘I don’t go south of the river’, may be traced back to a decision of Oliver Cromwell. In 1654 he licensed the ‘Fellowship of Master Hackney Coachmen’ who, in return for an annual licence fee of £5, enjoyed a monopoly of four-wheeled transport north of the Thames as far as the ‘New Road’ which is now the line of the Marylebone Road–Euston Road–Pentonville Road–City Road route. They enjoyed no such privileges south of the river which probably suited them since it had been a disreputable area to which undesirable people and activities had been banished by the authorities. Since, besides bear-baiting and prostitution, these included actors and theatres, the area south of the river, especially Southwark, is rich in literary connections, not least with William Shakespeare.

SOUTHWARK

Much of Little Dorrit is set in Southwark. The Marshalsea Prison for debtors, where John Dickens was confined during Charles’s time at the blacking factory, was for so long the ‘home’ of William Dorrit that he was known as ‘The Father of the Marshalsea’.

John Dickens (1785–1851) was the well-meaning but improvident father of the novelist, whose inability to manage his finances resulted in his incarceration in the Marshalsea Prison for debtors, in Southwark, and Charles’s despatch to Warren’s Blacking Warehouse near Hungerford Market, Charing Cross. It was later moved to Bedford Street, to the north of the Strand where Dickens’s humiliation was aggravated by his having to work in public view, applying labels to bottles. The shame of his father’s humiliation and his spell in the blacking warehouse haunted Dickens for the rest of his life, but did not prevent him from drawing on the experiences in his novels. The kind, optimistic but helpless Wilkins Micawber in David Copperfield is a thinly disguised portrait of John Dickens. However, Micawber would not have had John’s effrontery in approaching the novelist’s publisher, Chapman and Hall, to ask for a loan following the success of Pickwick Papers. No. 16, Bayham Street, Camden Town was one of John’s many homes and was the model for Bob Cratchit’s home in A Christmas Carol and for Traddles’s lodgings with Micawber. It has since been demolished but the site is marked by a plaque.

&nbs

p; Dorrit was the victim of an uncompleted contract with the Circumlocution Office, a portrait of officialdom and the legal system which rivals Bleak House in its bitter satire. In Little Dorrit the reader can feel the memory of Dickens’s childhood experience as he describes the prison:

Thirty years ago there stood, a few doors short of the church of Saint George, in the Borough of Southwark, on the left hand side of the way going southward, the Marshalsea Prison. It had stood there many years before and it remained there some years afterwards; but it is gone now, and the world is none the worse without it.

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop