- Home

- Stephen Halliday

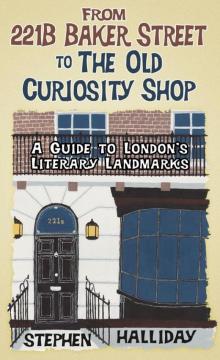

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop Page 13

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop Read online

Page 13

Dickens’s description of the Marshalsea in Little Dorrit was written in 1857, fifteen years after the jail was demolished, but his recollection of it during his family’s incarceration there in 1824 is clear and harsh:

It was an oblong pile of barrack building, partitioned into squalid houses standing back to back, so that there were no back rooms; environed by a narrow paved yard; hemmed in by high walls duly spiked on top.

In a preface to Little Dorrit, written shortly after the story had been completed, Dickens described how he had recently visited the site of the prison: ‘Whosoever goes into Marshalsea Court, turning out of Angel Court, leading to Bermondsey, will find his feet on the very paving stones of the extinct Marshalsea jail … and will stand upon the crowding ghosts of many miserable years.’ The streets have been somewhat altered since 1857 but the pedestrian can easily find Angel Place, as it is now called, Marshalsea Road and Little Dorrit Court, Angel Place being the site of a plaque fixed to the wall which used to mark the southern boundary of the prison. We can tread in Dickens’s footsteps but we can scarcely feel as he did as he visited a place he remembered with shame and horror until his death. So inured is William Dorrit to life in the Marshalsea that when he inherits a fortune and leaves the prison he has difficulty adapting to life outside and he dies in Rome on a continental tour following his release.

A little to the south of the Marshalsea, at the junction of Borough Road and Borough High Street, lay another debtors’ prison, the King’s Bench, to which Dickens sent Wilkins Micawber during one of his many brushes with financial embarrassment. There David Copperfield visited him and found Micawber ready to give birth to one of the most famous passages in the language:

Mr Micawber was waiting for me within the gate, and we went up to his room (top storey but one) and cried very much. He solemnly conjured me to take warning by his fate; and to observe that if a man had twenty pounds a year for his income and spent nineteen pounds nineteen shillings and sixpence he would be happy but that if he spent twenty pounds one he would be miserable. After which he borrowed a shilling off me for porter.

Just a little further to the south again, at the junction of Newington Causeway and Harper Road, is the Inner London Crown Court which stands on the site of the former Horsemonger Lane Jail. There, in 1849, Dickens was amongst a crowd who witnessed the execution of a married couple, George Manning and his Swiss wife Maria, who had murdered a former lover of Maria and buries the corpse, in quicklime, beneath their kitchen floor. Maria’s attempts to escape the consequences of a crime in which she had clearly been involved shocked the public, the execution drawing a crowd of 30,000 whose behaviour, ‘the shrillness of the cries and howls that were raised from time to time’, shocked Dickens. He may have drawn on his knowledge of the case to portray the murderous maid Hortense, in Bleak House who, like Maria Manning, was both foreign (French) and a former maid. The gravestones of the Mannings are now on display in the nearby Cuming Museum and Library in the Walworth Road.

Marshalsea Prison in Southwark was where Dickens sent the Dorrit family and Samuel Pickwick. It was also where his father, John Dickens, was committed. (Mark Beynon)

Just across Borough High Street, running parallel to Marshalsea Road, is Lant Street, which was for a time the home of both Charles Dickens and of the hero of his autobiographical novel, David Copperfield, the latter commemorated by Copperfield Street which stretches beyond Marshalsea Road. Mr and Mrs Garland in The Old Curiosity Shop are believed to be based on the author’s Lant Street landlord and his wife. Samuel Pickwick and his companions also enjoy the supper party given by the Guy’s Hospital medical student Bob Sawyer in his Lant Street lodgings. Dickens who, despite his father’s embarrassments, appears to have been very attached to the area and its residents, gave an affectionate portrait of the area in The Pickwick Papers:

There is a repose about Lant Street which sheds a gentle melancholy upon the soul … The chief features in the still life of the street are green shutters, lodging bills, brass doorplates and bell-handles; the principal specimens of animated nature the pot boy, the muffin youth and the baked potato man. The population is migratory, usually disappearing on the verge of quarterday [i.e. when rent was due] and usually by night. Her Majesty’s revenues are seldom collected in this happy valley; the rents are dubious and the water is very frequently cut off.

Other Dickens characters are also celebrated in street names including Trundle Street and Weller Street (both from The Pickwick Papers) as well as Little Dorrit Court and the church of St George the Martyr where Little Dorrit was finally married to Arthur Clennam and where she is commemorated in the church’s ‘Little Dorrit’ East Window. The ending of Little Dorrit, one of the most moving that Dickens wrote, tells how, at the end of the marriage ceremony, husband and wife:

Walked out of the church alone. They paused for a moment on the steps of the portico, looking at the fresh perspective of the street in the autumn morning sun’s bright rays, and then went down. Went down into a modest life of usefulness and happiness … They went quietly down into the roaring streets, inseparable and blessed; and as they passed along in sunshine and in shade, the noisy and the eager, and the arrogant and the forward and the vain fretted and chafed and made their usual uproar.

PILGRIMS AND POETS

The George Inn, off Borough High Street, also features in Little Dorrit and survives as London’s only galleried inn. It is sometimes (mistakenly) identified as the Tabard Inn from which Chaucer’s pilgrims set out in The Prologue to the Canterbury Tales:

It happened that in that season, on a day

In Southwark, at the Tabard as I lay

Ready to go on pilgrimage and start

To Canterbury, full devout at heart,

There came at nightfall to that hostelry

Some nine and twenty in a company

Of sundry persons who had chanced to fall

In fellowship and pilgrims were they all

That toward Canterbury town would ride.

The rooms and stables spacious were and wide

And well we there were eased and of the best

The verse reads almost like an advertisement for the inn!

The original Tabard certainly existed, along with its landlord, Harry Bailey. It was burned to the ground in 1676 and rebuilt as The Talbot, which retained the original gallery to be used by visiting theatrical troupes, especially during Southwark Fair which flourished from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century and was celebrated in Hogarth’s 1733 engraving of the event. The landlord of the renamed inn, presumably fearing that he was losing trade as a result of the name change, placed a placard across the entrance informing visitors that ‘This is the Inn where Sir Jeffrey Chaucer and the nine and twenty pilgrims lay in the journey to Canterbury, anno 1383’. The poet’s ghost was no doubt grateful for the knighthood posthumously conferred along with the name change, but it didn’t save the inn which was finally demolished in 1873. Its name is preserved on its original site, Talbot Yard, off Borough High Street on the approach to London Bridge. The George Inn nearby serves as a suitable proxy and was probably one of the coaching inns Dickens had in mind in The Pickwick Papers when he wrote of ‘great, rambling, queer old places with galleries and passages and staircases’.

The most prominent building in Southwark is Southwark Cathedral. Begun in 1220, it is the oldest Gothic church in London, having escaped the fire which consumed the City churches, on the opposite bank of the Thames, in 1666. It was originally a parish church, St Saviour’s, and did not become a cathedral until the new diocese of Southwark was carved out of the diocese of Winchester in 1897. It contains the tomb of Lancelot Andrewes, Bishop of Winchester, and one of the principal translators of the Authorised (‘King James’) version of the Bible which, with the plays of Shakespeare, is part of the architecture of the English language. On Christmas Day 1622, Lancelot Andrewes preached a sermon before King James himself at Whitehall Palace which, in reference to the three wise men

who visited Christ, contained the words:

A cold coming they had of it at this time of the year, just the worst time of the year to take a journey, and specially a long journey. The ways deep, the weather sharp, the days short, the sun farthest off.

These words were adopted and placed into the mouths of the Magi themselves by T.S. Eliot in the opening verse of his poem ‘The Coming of the Magi’, which the poet wrote at the time of his baptism and reception into the Anglican church in 1927:

A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.

And the camels galled, sore-footed, refractory,

Lying down in the melting snow.

There were times we regretted

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

The George Inn, off Borough High Street, is the only galleried inn left in London and was featured in Little Dorrit. (Ewan Munro)

THE GLOBE

Shakespeare himself, of course, has many associations with Southwark. Since theatres were banned from the City itself, as attracting undesirables like actors, they were built either outside the City precincts or in the particularly disreputable district across the river, on Bankside. The first was The Rose, which was built by Philip Henslowe, an impresario and entrepreneur, in 1587. Henslowe found brief fame when he was portrayed by Geoffrey Rush, in the film Shakespeare in Love, with a small part as ‘The Apothecary’ in Romeo and Juliet, a role for which the actor received an Oscar nomination. The Rose saw the first productions of Marlowe’s Tamburlaine and Shakespeare’s Henry VI Part I. Henslowe’s theatre enjoyed so much success that it was soon followed, and eclipsed, by The Swan and The Globe nearby. The Rose’s foundations were revealed during construction work in 1989 close to Southwark Bridge where there is now an exhibition.

The Globe was first built in 1576 close to the later site of The Curtain in what is now Curtain Road, Shoreditch. It was built by the actor James Burbage and prospered, but, following an argument with the owner of the land, Burbage and his company dismantled the theatre one night, moved it bodily across the river and re-erected it in 1599. One of the shareholders (and presumably therefore one of the removal men) was one William Shakespeare. Like many theatres of the time it had a relatively short life. It was destroyed by fire in 1613 during a performance of Henry VIII when two cannons were fired to welcome the arrival of the actor playing the king. The thatch caught fire and the theatre was destroyed. The only casualty was a man whose breeches caught fire and ‘put it out with bottled ale’.

The present Shakespeare’s Globe we owe to the American actor Sam Wanamaker, who was so moved by a replica of the original theatre which he saw as a young man at a fair in Chicago that he came to London to see the original. Learning that it had burned down three centuries earlier he set about reconstructing it, using the plans of the original theatre and, as far as possible, original materials (along with a few modern amenities like sprinkler systems). Its prominent site on Bankside is close to that of the original Globe whose foundations may be seen in the courtyard of some flats on Park Street nearby.

There was one notable exception to the ‘no theatres in the City’ rule and this exception was a source of great irritation to the City authorities, and to Shakespeare and his colleagues who were banished to the South Bank. In 1578 Richard Farrant, a composer of some fine church music which is still regularly performed, opened the Blackfriars Playhouse in his capacity as ‘Master of the Children of the Chapel Royal’. He argued that it was a theatre where choristers could practise ‘for the better training them to do her Majesty service’. Given his royal connections there was little the City fathers could do and when Farrant died in 1580 it was bought by James Burbage, father of the actor Richard Burbage, and turned into a private theatre, though it continued to be used by the choristers who, besides practising their singing, also performed plays. In Hamlet Act II scene II Shakespeare makes a bitter reference to ‘an eyrie of children … these are now the fashion and so berattle the common stages’. Richard Burbage, in company with six fellow actors, one of whom was Shakespeare, eventually took over the running of the theatre for his company ‘The King’s Men’, royal patronage once again helping to overcome any objections from the City. Many of Shakespeare’s plays were performed there until the theatre was closed by the Puritans in 1642 and demolished in 1655. Its site, however, is marked by Playhouse Yard, off Blackfriars Lane.

LAMBETH

To the west of Southwark, in the borough of Lambeth, is Waterloo station, which features in Jerome K. Jerome’s (1859–1927) Three Men in a Boat (to say nothing of the Dog), published in 1889. The book begins with an account of the hypochondriac narrator’s visit to the British Museum library to establish the cause of a mild illness: ‘I remember going to the British Museum one day to read up for treatment for some slight ailment … the only malady I could conclude I had not got was housemaid’s knee.’ The three friends, Jerome, George, Harris and Montmorency (the dog), decide to row from Kingston to Oxford to restore their health and begin by going to Waterloo to take a train for Kingston:

We saw the engine driver and asked him if he was going to Kingston. He said he couldn’t know for certain of course but that he rather thought he was … We slipped half-a-crown into his hand and begged him to be the 11.15 for Kingston … ‘I suppose some train’s got to go to Kingston and I’ll do it. Gimme the half-crown …’ We learned afterwards that the train we had come by was really the Exeter mail and that they had spent hours at Waterloo looking for it.

(This claim of course overlooked the fact that it is the signalman, not the driver, who decides the destination of a train.)

Jerome’s later work Three Men on the Bummel is set in Germany but begins just along the Thames from Waterloo where George stops to buy boots near Astley’s amphitheatre, a circus venue at 225 Westminster Bridge Road where Robert Martin and Harriet Smith had earlier come to an understanding with each other out of reach of the well-meaning interference of Jane Austen’s Emma who was determined to choose Harriet’s husband on her behalf. Jane Austen herself had visited the establishment in 1794. Jerome K. Jerome’s narrator explains:

We stopped the cab at a boot shop a little past Astley’s theatre that looked the sort of place we wanted. It was one of those overfed shops that the moment their shutters are taken down in the morning disgorge their goods all round them. Boxes of boots stood piled on the pavement or in the gutter opposite.

When George asks if he can buy some boots the reaction of the proprietor is less than welcoming: ‘What d’ye think I keep boots for, to smell ’em? Did you ever hear of a man keeping a boot shop and not selling boots? What d’ye take me for, a prize idiot?’

After visiting Bucklersbury, opposite the Bank of England in the heart of the City, to hire a yacht to take them to the Continent, the party returns to a small shop in the Blackfriars Road, east of Waterloo station, so that George can buy a cap. George explains to the shopkeeper that he wants ‘A good cap’. Once again he receives a discouraging reply:

Ah, there I am afraid you have me. Now if you had wanted a bad cap, not worth the price asked for it; a cap good for nothing but to clean windows with I could have found you the very thing. But a good cap – no, we don’t keep them.

Poor George: bootless and capless.

To the south, still in the borough of Lambeth, is Walcot Square. Virtually unaltered since the time of Charles Dickens, it is in fact a triangle in which, in Bleak House, Mr Guppy leases ‘a commodious tenement, a six-roomer’ during his unsuccessful pursuit of the heroine of the novel, the saintly Esther Summerson.

Further to the west, still in Lambeth, is St Thomas’s Hospital where, in the 1890s, Somerset Maugham worked as a medical student and junior doctor. This was an area noted for violent crime and Maugham left an account o

f his work in the area as he travelled, on foot, to some of its darkest areas to minister to the poor and, in particular, to deliver babies. He felt perfectly secure because he was protected by his ‘Gladstone bag’, a portmanteau which carried medical instruments and supplies and which was recognised as that of a doctor, a profession viewed with respect even in the poorest areas. Maugham’s first novel, Liza of Lambeth (1897), draws on his experience. It is the story of Liza Kemp, a factory girl, the youngest of thirteen children, who enters into an adulterous relationship with Jim Blakeston, a 40-year-old married father of nine by whom Liza becomes pregnant. Domestic violence is a frequent occurrence in the lives of the characters, often fuelled by drink and one of the novel’s most dramatic episodes occurs when Jim’s wife attacks Liza, cheered on by a baying crowd of women. Liza dies following a miscarriage, an episode the young Somerset Maugham must often have witnessed. Liza’s home is in Vere Street, a fictional street off Westminster Bridge Road with which the young doctor was thoroughly familiar.

007 AND FIREWORKS

To the south of Westminster Bridge Road is Vauxhall Cross, the headquarters of MI6 now standing brazenly on the banks of the Thames. Now the home of James Bond, ‘M’, ‘Q’ and the other characters made famous by the novels of Ian Fleming and the films which followed, the building did not exist in Fleming’s lifetime (indeed MI6 itself, the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), had no official existence until 1994). Fleming himself worked for the SIS during the Second World War when it was based at 54 Broadway, near St James’s Park.

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop

From 221B Baker Street to the Old Curiosity Shop